Payton Capital Economic Update March 2023

The current economic environment remains uncertain. Has enough (or too much) been done by the RBA to curb inflation? How long will it take to find out? Will the unemployment rate rises before inflation is controlled? Could global events swamp the best intentions of Australia’s central bank once again? And are there opportunities for investors in the property sector right now?

“It is a complex environment in which to be making policy decisions, with many of the variables we monitor at or near record highs or lows,” the RBA Governor Lowe confided in March.

But there is great reason for hope, with unemployment holding at low levels even as inflation begins to fall, and business conditions surveys reporting an ongoing strong operating environment.

Signs have begun to appear in the Australian economy that interest rates are doing their job. In January for the first time since 2021 an inflation number appeared that was meaningfully lower than the one preceding it. Unemployment also ticked up in January, and the falling housing market cemented the picture: official interest rates were functioning as expected.

However, the strong data from February’s labour force report complicated the picture of an economy grinding slower: Unemployment fell as tens of thousands of people found full-time work. The ongoing strength in the labour market raises a hopeful question: Is it possible rates could be working to cool consumer inflation without damaging the labour market business conditions unduly?

Most recently, rates markets began to pencil in a rate cut by the end of the year. Increasingly it looks like the key turning points are behind us or in sight, whether we look at inflation, interest rates or the property market.

In property, in addition to a turning macroeconomic environment a surge in migrants is likely to provide a strong underpinning to demand and in turn we expect to see prices moderate and even rise in the coming year.

WHAT HAVE WE SEEN?

Consumers

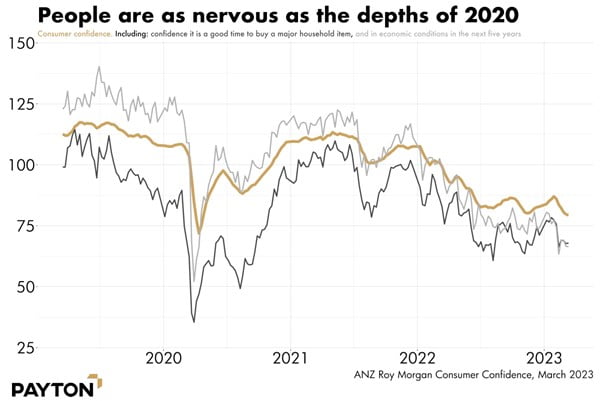

Currently we are seeing a disconnect in consumers words and actions. It has been widely reported that consumer confidence remains low, and is equivalent to the uncertain times of the start of COVID-19 in mid-2020 and the GFC before this as the ANZ Roy Morgan consumer confidence survey shows:

The sentiment is plausible, with inflation (unprecedented for those under 45 years old) creating very visible day-to-day problems for consumers, while interest rates are very rapidly rising to levels borrowers may not have anticipated when taking out their loans.

Evidence on the ground for consumer despair is much thinner, with generous spending on travel and dining still apparent in the official data. Still, Christmas spending was subdued, even accounting for a shift in consumer spending patterns to the big online sales in November (Black Friday sales).

Major retailers report a slowing but are not sounding the alarms just yet. The impact of higher interest rates on household budgets is not blindingly obvious but it is safe to say it may be taking the edge off.

The expected impending “fixed rate interest rate cliff” could mean more consumer belt-tightening remains in prospect. As fixed mortgages expire, households will be paying a much higher variable interest rate. Scheduled mortgage payments are set to rise 50 per cent for most households whose fixed interest period expires. This phenomenon is set to play out over the coming months, with over $400Bn of fixed rate mortgages set to roll onto variable rates during the remainder of 2023, and a tail of mortgages doing so in 2024. Overall, scheduled home loan repayments as a share of disposable income will be back to pre-GFC highs by the end of the year, which should cool the consumer economy.

INFLATION

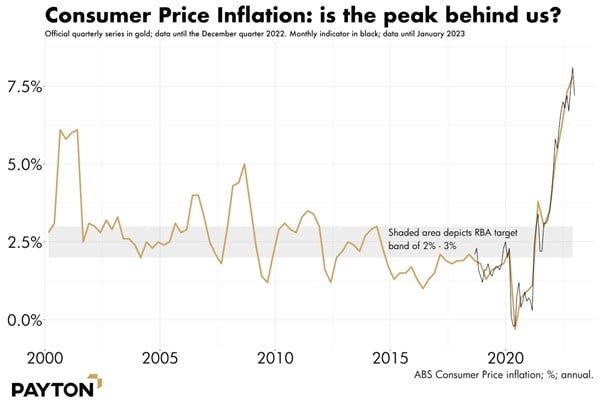

December’s quarterly inflation data, as forecast, delivered the highest inflation number seen in decades. But at 7.8 per cent, it was not as high as the peaks seen in much of the rest of the world (the UK managed 11 per cent), and the monthly indicator data that came out the very next month was lower, recording YoY price growth of 7.4 per cent.

Other countries put their highest inflation period behind them in late 2022 and we believe Australia has done so as well. After all, some of the forces driving prices higher at ever-more-terrifying rates are now in abeyance, as we will discuss in the next section. Prices for goods like clothing are falling, while prices for domestic services like travel are rising.

The good news is, the RBA forecasts inflation to fall to 4.8 per cent by the end of 2023 and 3.2 per cent by the end of 2024, a similar timeframe to most other countries. Inflation expectations remain in check, suggesting the forecast is achievable.

UNEMPLOYMENT

Australia’s unemployment rate remains blissfully low. It rose from record lows of 3.4 per cent in late 2022 to 3.7 per cent in January, but the ABS observed a statistical anomaly in that month: many people said they had a job confirmed to start in February. That proved accurate, with large flows into employment in the second month of 2023. The unemployment rate duly slid back down. Any fear of a labour markets collapse seems, for now, unwarranted – the RBA has not yet cooled the economy enough to put a lot of people out of work.

Youth unemployment is at record lows and so is underemployment – people are getting the hours they want. The long-term benefit of this period should stay with us. Economists like to talk about “hysteresis” – the lasting effects of a period of unemployment, as people lose labour market skills, etc. But hysteresis works both ways: short unemployment queues mean more people whose contact with the labour market starts early in life and is consistent. The longer this period of low unemployment lasts, the greater the benefit.

Despite the low rates of unemployment, we are still keeping a lid on wages growth. That’s good news, as the RBA governor explained in March. “If prices and wages were to chase one another, the end result would be persistently high inflation, even higher interest rates and higher unemployment,” he said. Happily, however, “the risk of a prices-wages spiral remains low.” This fact allays one of our greatest concerns and provides us with a source of great optimism that this period of high inflation can be temporary, and the economy can return to an even keel – with a strong labour market still in place.

WHERE ARE WE NOW?

Global Price Pressures

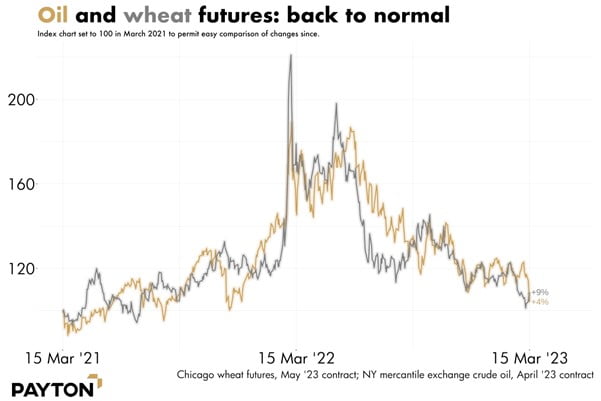

The global price pressures that led the world into inflation are now basically gone. Shipping prices have normalised, while wheat and oil futures have reverted, as the next chart shows. It’s all about domestic issues now.

That trend is visible also in ABS consumer price data. Non-tradable goods are now rising in price faster than tradable goods. This is the case even though the latter category includes international travel, for which Australians have a very strong appetite!

Instead of importing higher prices, we are now importing market gloom, thanks to US recession risk and financial wobbles. Silicon Valley Bank – a Californian entity with significant tech exposures – collapsed in March. The US government bailed out depositors but not before the collapse had the opportunity to send fear through markets in tech and finance. In Europe, Credit Suisse also needed bailing out with the merger between it and UBS all but complete.

That risk of financial contagion is enough to have markets second-guessing the US Federal Reserve and whether it will continue to raise rates. Rate rises that drove down asset prices was a major factor in rendering Silicon Valley Bank insolvent, and so a pause in rate hikes may be appropriate to help stabilise other medium-size US banks in the short run.

It is important to recognise this is not a repeat of 2008, because the banks involved are not enormous systemically important entities, and because the risks are not on the lending side so much as the deposits side. Silicon Valley Bank didn’t make bad loans – instead this was a classic bank run. Where it went bad was that when it liquidated assets to repay deposits its capital was worth less than hoped due to recent falls in asset prices.

Australia’s situation is different to the US, with few mid-size banks and a smaller tech sector. Our financial sector is more stable and Big 4 Banks hold ample capital buffers. Our recession risk is also much lower as interest rate changes gain more traction sooner in Australia via variable rate mortgages. In the US, most mortgages lock in rates for 30 years and so official rate changes hit a much smaller share of household budgets. Instead, US monetary policy works mostly by deflating asset prices, including the share market. That means the Federal Reserve may need to throw the economy into recession to halt inflation. In Australia that’s not likely to be necessary.

WHAT DO WE SEE?

House Prices

As interest rate rises come towards their end – Payton’s view is one more hike is the most probable outcome. It is also interesting to note that markets are pricing in rate cuts by late 2023 and with this the period of gloom in Australian housing seems set to end (once again).

The market that led Australia’s house price falls – Sydney – is now seeing some price stabilisation. According to Corelogic data, Sydney house prices were steady in the most recent four-week period.

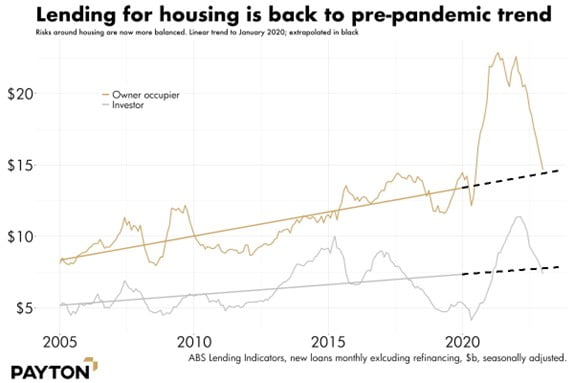

While some further price falls are probable in most Australian markets, the risks around housing are now far more balanced. Lending for home purchase has retracted its pandemic era boom to be back on pre-pandemic trend levels, as the next chart shows.

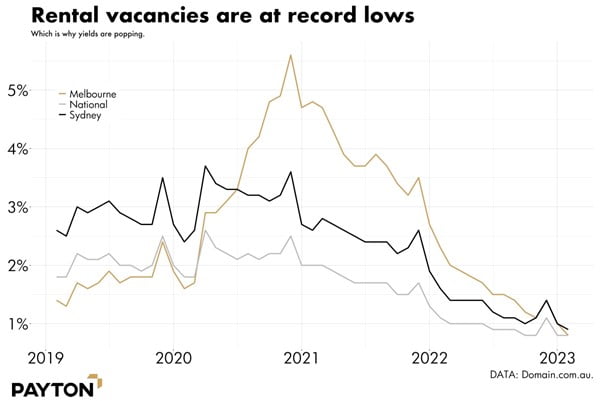

A record 106,000 migrants came to Australia in the third quarter of 2022. Some 240,000 people are expected to migrate to Australia in the next year, which is close to record levels. They will arrive in a country where rental property is very hard to find. As the next chart shows, rental vacancies are very low indeed: less than one in every 100 properties is vacant.

Migrants are generally adults and need housing immediately (unlike the other category of additions to the population, who may live with their parents for decades!)

Inflation in advertised rents has been very high. Combined with falling property prices, yields on rental housing are rising significantly. We expect to see investor interest in property return, especially since rising interest rates make negative gearing a more realistic prospect.

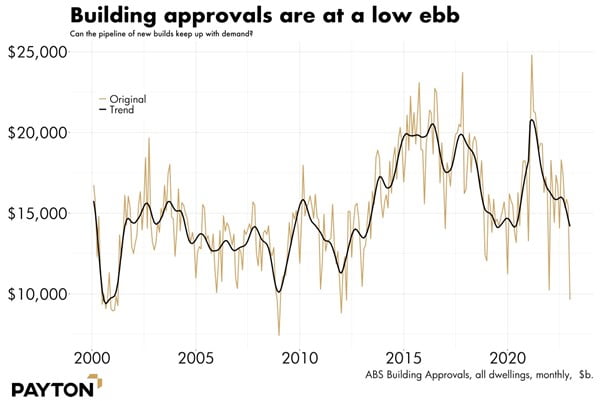

If demand rises for rental properties, the market will react by building more of them especially with the lack of starts over the Covid 19 lockdown periods. Such a reaction does not happen overnight, meaning there is a likely period where supply does not meet demand and prices rise. Currently the pipeline of building approvals is drying up in reaction to falling property prices, as the next chart shows but we expect to see this trend reverse as demand spurs on developers to take the risk and start new projects.

In a tight labour market, finding the tradespeople to build new apartments is a challenge. This is especially so in markets like Melbourne where significant investment in public infrastructure (Victoria Government Big Build) is providing demand for such workers.

What is likely to happen is a period of acute rental housing shortfall and rapidly rising rents and in turn likely price appreciation as investors seek premium yields once again.

“A number of demand- and supply-side factors have contributed to the current tightness in the domestic rental market, with strong growth in rents expected over coming years,” the RBA observes.

CONCLUSION

If the RBA gets everything right, inflation should drift downwards as house prices stabilise, all without seeing the unemployment rate rise to an uncomfortable high. That should let markets get comfortable with building new housing to accommodate waves of migrants and home seekers. While events may yet nudge the economic narrative from its path, we believe we are at the beginning of the end of the battle against inflation and the economy is on a path back to a more stable, familiar economic environment.

For more information please contact Craig at craig.schloeffel@payton.com.au

Disclaimer: The information contained in this document is of a general nature and does not take into consideration the investment objectives, financial circumstances or needs of any particular recipient – it contains general information only. The views expressed in this document are solely those of the author and are subject to change without notice. Any financial projection and other statements of anticipated future performance that are included in this document are for illustrative purposes only and are based on assumptions that are subject to risks and uncertainties and may prove to be incomplete or inaccurate. Actual results achieved may vary from the projections and the variations may be material. Before deciding to make an investment with Payton, you should carefully read all of the information in the relevant Fund Information Memorandum, and consult with your business adviser, financial planner, accountant or tax adviser. Reliance upon information in this document is at the sole discretion of the reader. Payton Capital Ltd is an authorised representative of Payton Funds Management Pty Ltd ABN 32 107 613 258 AFSL 284280

About the author

~~ News & Insights ~~

Payton Capital Quarterly Economic Update September 2024

By Craig Schloeffel|2024-10-01T16:44:22+10:00September 24, 2024|

Payton Capital Quarterly Economic Update June 2024

By Craig Schloeffel|2024-07-02T17:01:11+10:00June 21, 2024|

Payton Capital Announces Acquisition by ASX Listed HMC Capital

By Jodie Elg|2024-06-21T13:10:25+10:00May 24, 2024|

Payton Capital Quarterly Economic Update March 2024

By Craig Schloeffel|2024-07-02T17:07:49+10:00March 28, 2024|

Payton Capital Quarterly Economic Update December 2023

By Craig Schloeffel|2024-07-02T17:10:56+10:00December 15, 2023|

Media Release: Payton Capital’s Queensland Expansion

By Jodie Elg|2024-06-21T13:20:44+10:00October 20, 2023|

Payton Capital Quarterly Economic Update September 2023

By Craig Schloeffel|2024-07-02T17:14:08+10:00September 28, 2023|

Australia’s Housing Crisis is on the Verge of Imploding

By David Payton|2024-06-21T13:25:40+10:00July 4, 2023|

Payton Capital Economic Update June 2023

By Craig Schloeffel|2024-07-02T17:16:49+10:00June 30, 2023|

Foresight Analytics Upgrades Payton Capital’s Operational Due Diligence

By Jodie Elg|2024-07-02T17:37:28+10:00June 12, 2023|

Payton Capital Economic Update March 2023

By Craig Schloeffel|2024-07-02T17:20:11+10:00March 23, 2023|

Payton Capital Quarterly Economic Update December 2022

By Craig Schloeffel|2024-07-02T17:23:33+10:00December 12, 2022|